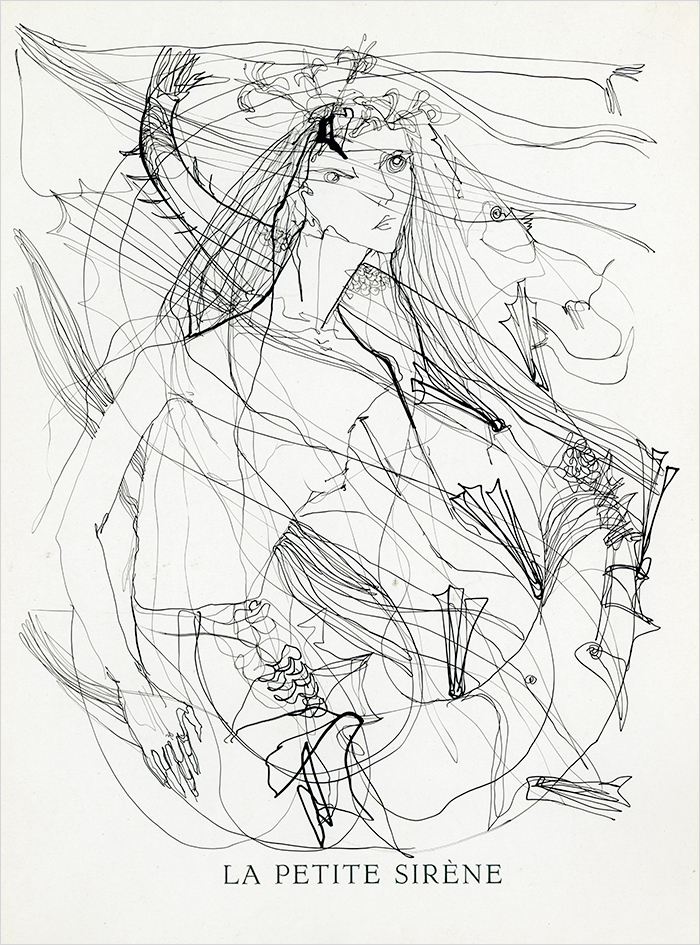

Françoise Taylor drawings

"It is not enough to render by a drawing a definite passage of a literary work. It is necessary that this single drawing renders at the same time all the atmosphere of the subject and all the temperament of the writer. This tour de force, Françoise Wauters succeeds." Paul-Henri Bourguignon (1906–1988), visual artist and observer of the human condition.

"These are not pictures to hang on the wall and forget in a week or two. Though at first sight they appear decorative, they compel another kind of attention, and the more one looks the more the compulsion grows." The Guardian, 1950s.

THE ART OF DRAWING is at the heart of almost everything Françoise Taylor produced during over half a century as an artist. It began in 1937, when she was seventeen, with several years of life drawing study at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels (the Belgian version of the British Royal Academy). She almost never drew in pencil. Her main tools of choice when she moved to 'La Cambre' (the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d'Architecture et d'Arts Decoratifs, also in Brussels) were the burin, the etcher's needle and the woodcutter's gouge, and sometimes the pen.

Bird with spider, etching, 1947

Actual size: 197mm high x 241mm wide

She excelled at drawing from the start. At the Académie Royale she won the First Prize for Drawing three years in succession. At La Cambre, where she specialised in engraving and typography, she became the first in Belgium to win a Distinction and a Mastery in Book Illustration awarded by a jury of seven of Belgium's leading art critics with "the greatest congratulations."

Drawing by Françoise Taylor, 1945/46

Actual size: 285mm high x 210mm wide

Françoise had by then developed a distinctive style of drawing that was uniquely hers, characterised by line quality and often the distortion of form to create flowing compositions sometimes very simple, sometimes swirling with depth. It was not only line but a combination of line with finely hatched modelling or tone lightly applied with a brush or other implement.

She had a remarkable gift for getting things right with few of the exploratory lines typical of an artist's drawing. Her representation of hands, for instance, are almost invariably perfect, accurate yet expressive, with no margin for error in her chosen medium. The medium of engraving was not actually her first preference. From an interest in representational form she entered La Cambre after passing a sculpture examination but was advised by her father to study book illustration, presumably as a potentially more lucrative career. Françoise was never much interested in a career. If anything, she intended to become a religeuse.

Ceci est mon corps | Calendrier des Pauvres d'Esprit

In 1946, however, Françoise met Englishman Kenneth Taylor in Antwerp at the home of Joris Minne, her tutor at La Cambre. Minne was a Belgian illustrator who helped to revive the art of wood and copper engraving in Belgium. To his disgust Françoise and Kenneth were married in Brussels in 1946 and she emigrated to England. Minne refused to even look at her work for the next six months. Nevertheless she went on to complete her Mastery in Oxford in 1949 by sending to Brussels a large portfolio of engravings, etchings, woodcuts, monoprints and lithographs as illustrations for Le Morte d'Arthur (Sir Thomas Malory), The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (Samuel Taylor Coleridge), a Baudelaire poem about cats, The Idiot (Dostoievski), The Basement Room (Graham Greene) and Æsop's Fables.

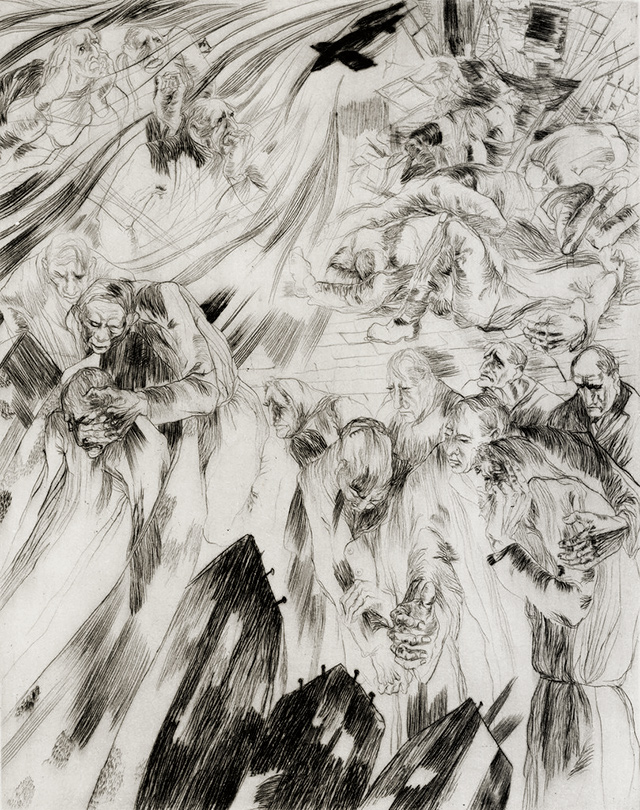

Her formative years as an artist in Belgium during the 1940s coincided with the German Occupation and the allied bombardments of 1944 and 1945. More than 1.5 million Belgians had left the country but she and most of her family remained in Brussels – she was a young female artist working in what effectively became a war zone. She witnessed first-hand the Deportations and the deprivations inflicted on the population. These are represented in a series of thirteen drypoints titled 'La Guerre' which she completed in August 1945. A complete set is in the permanent collection of the Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester along with other examples of her work.

V1 from 'La Guerre', 1944

Actual size: 392mm high x 292mm wide

By the time Françoise Taylor left Belgium at the age of 26 she had already produced hundreds of images – in print or book form – inspired by a wide variety of European literature from Shakespeare to obscure medieval texts, or by her Catholic religion, or by reality, or simply by her remarkable imagination.

Floere het Fluwijn | Chemin de Croix

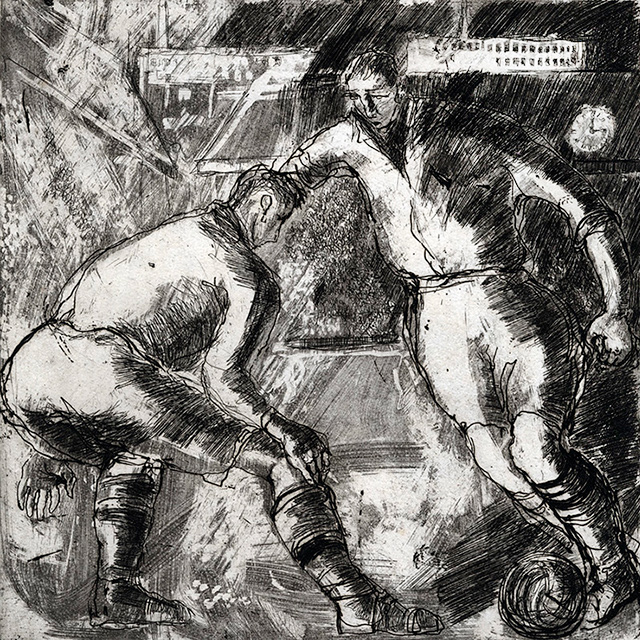

After a couple of years in Oxford she moved to Bolton in North West England – her husband's home town, an environment she began to illustrate with the fascinated unfamiliarity of an 'outsider': a post-war industrial landscape of mills, back streets, gasworks, coal mines, park bandstands and football crowds at Burnden Park, then the home of Bolton Wanderers.

Kick-off at Burnden Park, engraving, mid 1950s

Actual size: 278mm x 278mm

Françoise continued producing engravings until the mid-1950s. The plates were sent to London for printing. Perhaps she found this too time-consuming, or expensive, or being busy raising five children she wanted more immediate results. Either way, her practice of engraving eventually tailed off in favour of larger pen-and-ink drawings combined with watercolour which she created from sketchbooks she recorded while wandering the local streets. She painted a few hundred pictures of industrial Bolton during the 1950s and 60s – many still exist as a pictorial record of a cotton town just as textile manufacturing in England began to enter its dying years. The pictures were exhibited in various towns in the North West and sold well (there are a few examples in the permanent collections of Manchester Art Gallery and Bolton Art Gallery).

Engraving: Bolton Street [ examples ] Painting: industrial Bolton

Inevitably, as she grew older, the firmness of hand Françoise enjoyed in her twenties became less firm and her lines more meandering (if no less expressive). Her eyesight deteriorated to the point where she experienced constant double-vision. Neither of those limitations dampened the will to draw or to continue expressing her favourite literary themes – especially Alice in Wonderland, and now Romeo and Juliet, Venice, Ophelia and the 'pool of tears' – sometimes several themes combined into one. She drew in crayon on coloured paper: dreamy pictures she gave away as presents and continued each year with the Christmas cards she'd been drawing ever since coming to England.

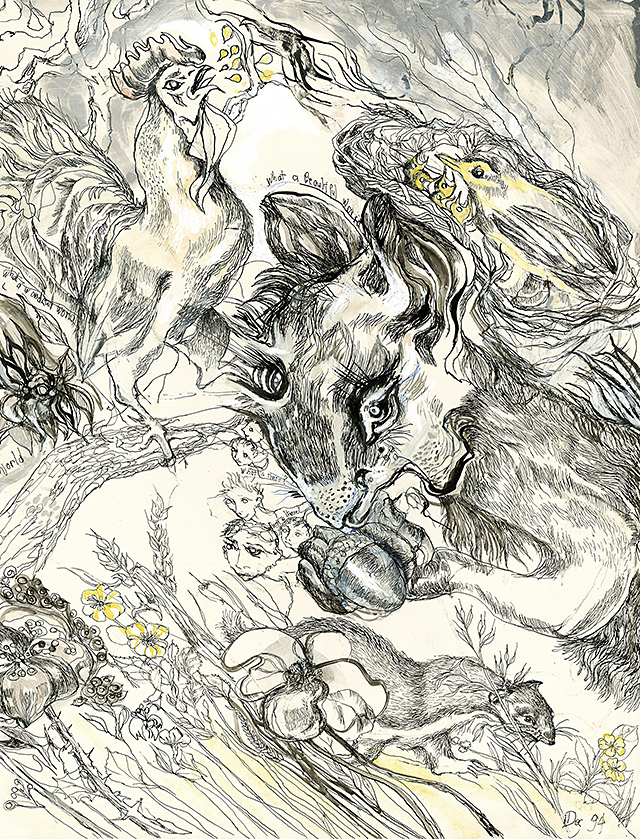

'What a beautiful world' (1994)

Françoise Taylor was still drawing in her late 70s. In 'What a beautiful world' human children emerge into a naturally harmonious world of animals and vegetation. She had probably loved the animal world more than the human version with our endless capacity for deliberately heaping hardship and misery upon each other.

A number of Françoise Taylor's etchings, engravings and drawings are held in the permanent collections of the Cabinet des Estampes of the Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris (National Library of France) and the Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique (Royal Library of Belgium) as well as in the hands of private collectors. They have also been exhibited in Paris, London, and other towns and cities in Belgium and the United Kingdom. Her works in The Whitworth's permanent collection in Manchester can be viewed by appointment.